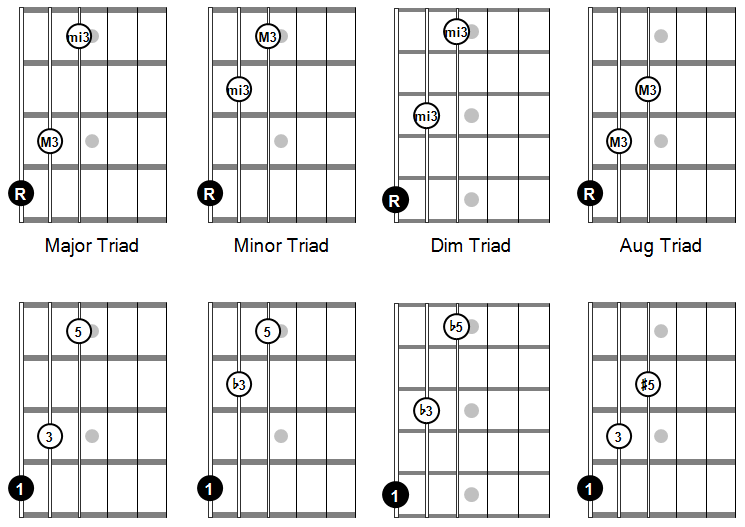

Basic chords are called triads and they are made up of three notes, but also two intervals. These intervals are thirds. Thirds come in two varieties: major or minor. A major third is equal to four half-steps (from E to G#), and a minor third is equal to three (from E to G). That means there are four different ways to stack thirds to get different kinds of chords:

Major: 1 – 3 – 5, major third + minor third (e.g. C-E-G)

Minor: 1 -♭3 – 5, minor third + major third (e.g. C-E♭-G)

Diminished: 1 -♭3 -♭5, minor third + minor third (e.g. C-E♭-G♭)

Augmented: 1 – 3 – #5, major third + major third (e.g. C-E-G#)

If we can learn to understand these basic intervals and apply it to our fretboard we will be able to play every major, minor, diminished, and augmented triad. Major and minor have opposite thirds, only the order is different, while augmented and diminished have two of the same thirds. This also means that major and minor triads are the only triads that have perfect fifths. Knowing how these chords are built can help you figure out what key you’re in as well. If we remember our roman numerals, we know that in a major key the order of chords is:

I-ii-iii-IV-V-vi-vii° – (maj, min, min, maj, maj, min, dim)

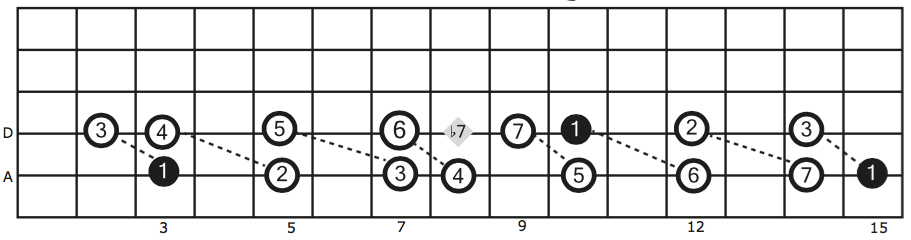

Our roman numerals come in handy because if it is capitalized we know the first third is major, and if lowercase we know it is minor. With this knowledge, let’s find the first half of our chords, the interval between the first and the third, in the key of C major:

| Min Thirds | Maj Thirds | Maj Thirds | Min Thirds |

| 7-2 | ♭7-2 | 5-7 | 5-♭7 |

| 3-5 | ♭3-5 | 1-3 | 1-♭3 |

| 6-1 | ♭6-1 | 4-6 | 4-♭6 |

| 2-4 | ♭2-4 |

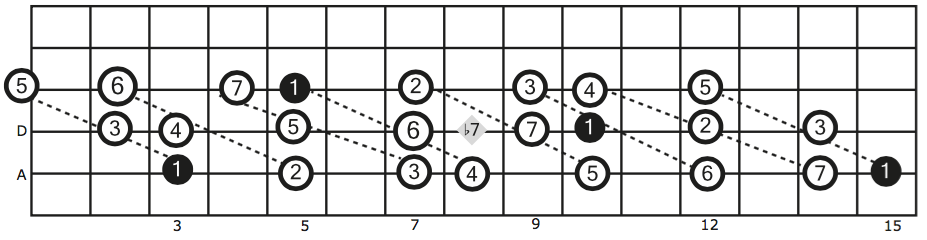

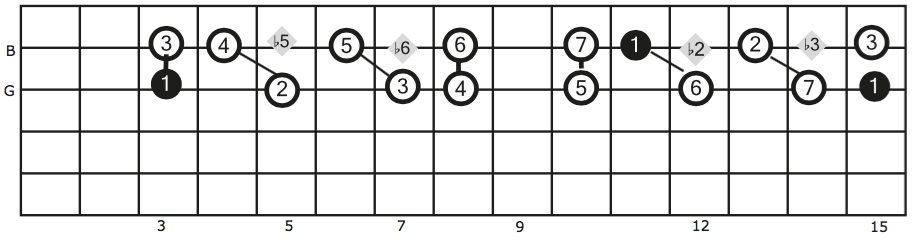

Here’s a look at the portion of the fretboard but in C minor:

Similarly, we know the only major triads here are the III, VI, and VII built on the ♭3, ♭6, and ♭7. We can see the same major triad pattern here by moving one fourth up and one half-step down, while the rest of the intervals are minor thirds, or one fourth up and two half-steps down.

Harmonizing a Major Scale

Building chords from each degree of the major scale is referred to as scale harmonization. We can use our knowledge of stacking a third, to build a major triad (Root + Major Third + Minor Third) using the intervals of a major scale (7-3-6-2-5-1). We can tell from our roman numerals that a chord that is major (i.e. IV) will have a minor third interval on top, because major and minor chords have opposite thirds (one major and one minor). If the first third was major, the second one is minor, and vice-versa. Take a look below at C major with complete triads:

See how the patterns change for the second interval? Let’s look at our I, IV, and V chords again. The major third pattern is visible from before, but they all have identical minor third patterns stacked on top. Likewise, the reverse is true for the minor triads, like ii, iii, and vi. The exception here is the vii° chord, which is neither major nor minor but diminished. We can visibly see that the triad built off of the 7 has two minor third intervals and no major thirds.

Let’s look at this same pattern again but with all of the fourths shown:

Using the NANDI method, we can see a major third is one fourth up and one half-step down, while a minor third is one fourth up and two half-steps down. Simply reverse this pattern when moving the opposite direction, i.e. a major third is one fifth down and one half-step up.

Knowing these facts you can tell whether a chord is major, minor, augmented or diminished just from looking at it. Below we’ll do the same thing but in the key of B♭ on our G, B, and E strings so you can see how the pattern differs visually when going across the B string:

Right away we can see by looking at our I, IV, and V chords that the major third pattern is as simple as moving up one string because of the fact the B string is tuned one half-step lower relative to the other strings. We’ve encountered this throughout the NANDI Method. Likewise, the minor third pattern now looks like the major third pattern from before, also because of the half-step difference in the B string.

When we stack the second interval on top it looks like this:

It’s clear the pattern when crossing the B string is visually different, but as long as you understand that the B string is one half-step off from the rest of the strings you will remember that every pattern you know changes by one half-step when you reach the B string. Soloists in particular may want to become familiar with these patterns on the fretboard as knowing chord positions in the upper register while soloing is indispensable.